by f. Luis CASASUS, General Superior of the mens’ branch of the Idente Missionaries

New York, June 14, 2020. | The Most Holy Body and Blood of Christ – Solemnity.

Book of Deuteronomy 8: 2-3.14b-16a; 1 Corinthians 10: 16-17; Saint John 6: 51-58.

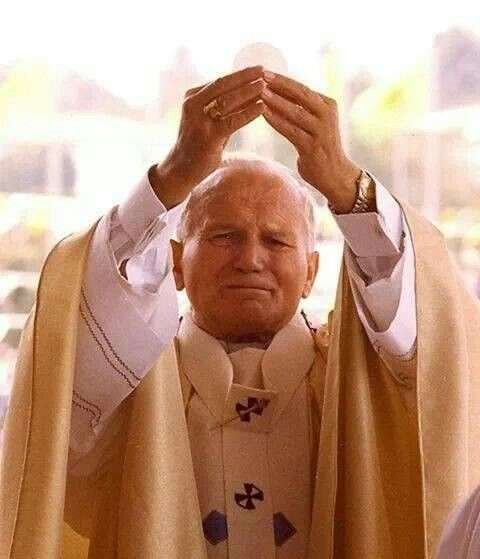

Dominic Tang, the courageous Chinese archbishop, was imprisoned for twenty-one years for nothing more than his loyalty to Christ and Christ’s one, true Church. After five years of solitary confinement in a windowless, damp cell, he was told by his jailers that he could leave it for a few hours to do whatever he wanted. Five years of solitary confinement and he had a couple of hours to do what he wanted! What would it be? A hot shower? A change of clothes? Certainly a long walk outside? A chance to call or write to family? What would it be, the jailer asked him. I would like to say Mass, replied Archbishop Tang.

Do we show that enthusiasm for the Eucharist, those of us who can receive it without difficulty, even every day? Indeed, for many of us, privileged Catholics, and especially the religious, it can be a danger to consider receiving the Body of Christ as a mere obligation or as a routine. In the months of the pandemic, listening to some parishioners or receiving emails from many people, I have been moved by their desire to receive the Holy Eucharist, something which for me personally is not difficult because we are privileged to have it in our chapel. Today is a day to remember the unique value of this Sacrament.

If a mouse were to eat the sacred host that falls on the ground, will it become a holy mouse? Similarly, if we receive the Eucharist without being prepared, without prior reflection, or even being completely distracted, it is difficult to believe that it is spiritually useful to us. It is like a student who is sitting at his school desk but his head is in a very different place.

St. Paul reminds us of this in an aggressive, almost threatening way: Let each one, then, examine himself before eating of the bread and drinking from the cup. Otherwise, he eats and drinks his own condemnation (1 Cor 11:28-29).

But this difficulty in taking advantage of the Eucharist has not just started either today or yesterday. We can see it the very moment Jesus taught the disciples saying, I tell you the truth, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in you (Jn 6: 53). Instantly a group of people went away from him saying: This is a hard teaching. Who can accept it? And no longer they followed him.

Our Father Founder says in the Catechism of the Confessor:

The Eucharist has precisely three purposes: to give the preventive grace against sin; to give the grace of the purpose of amendment; to give the grace of the moral certainty of going to heaven.

Societies’ practices for dealing with health and antisocial behavior problems are mostly reactive. Normally, these problems are dealt with once they have arisen. A major advance in reducing the incidence and prevalence of problems of health and human behavior becomes possible with the development of prevention sciences.

We are capable of believing in the value of prevention in the affairs “of this world” and, paradoxically we do not benefit from the value of the Eucharist, the graces it gives us to prevent sin, discouragement in conversion and doubts about whether we are admitted to the kingdom of heaven.

Believing in the presence of Christ in the Eucharist does not mean any theological subtlety. It is a matter of taking advantage of the intention that Jesus had in establishing that presence. We have just mentioned the preventive value in the face of the reality of sin. But also, by giving us the assurance that we can live out our purpose of amendment (actual conversion) and our contribution to the kingdom of heaven.

This is how our Founding Father declares it:

If there is a truly medicinal sacrament, it is the Eucharist. This sacrament is given for the development of all the genetic values of human life; its mission is to correct the pathological (1991)

The Eucharist is the bond or the ring that unites us all to each other, and to Christ. And forming one single life, to the extent that the examination that will be made to every member of the Institute at the hour of death is: how did he live the Eucharist? And in the light of what it is, one will see the fruitfulness or infertility, and the spirit that the member had of the Institute (February 26, 1961).

In one of his sermons, Saint Augustine said that, when the priest prays before the bread on the altar, it is not that the priest is saying that, by virtue of this prayer, this ordinary bread is now transformed into an extraordinary sacrament. It is rather that, in praying the Prayer of Thanksgiving at the altar, the priest acknowledges bread as a gift of a loving God and therefore that it is holy, part of a sacrament. This is why in the Preparation of the Gifts we say:

Blessed are you, Lord God of all creation, for through your goodness we have received the bread we offer you: fruit of the earth and work of human hands, it will become for us the bread of life.

Yet the bread of breakfast is different from the bread that is the body of our Lord in the Eucharist. At the Lord’s Supper by faith we are made participants in God’s body so that the world may know that the world can move forward only with the divine presence. We are incorporated into the enterprise of God’s salvation of the world. Through this meal, God unites us with one another in a mystical bond. The table, a loaf of bread, the wine, become expressions of the way God is penetrating the world, claiming it as his own.

Whenever we enter a chapels or a temple sees the only bread in two forms, or the double table: the altar of the Eucharist, the lectionary of the Word. The Second Vatican Council has recalled it: The Church has never failed to take the bread of life, taking it from the table both of the Word of God and the body of Christ and offer it to the faithful (DV 21).

Receiving Holy Communion is not equivalent to performing a magic ritual. When one agrees to become one person with Christ in the sacrament, must be aware of the proposal made to him, and take a firm decision to accept it. The gesture to reach out to receive the consecrated bread is the sign of the interior disposition to accept Christ and to ensure that his thoughts become our thoughts, his words our words, his choices our choices. In the Eucharist, his person is assimilated, as is the case with the bread.

In the First Reading, the book of Deuteronomy aims to give light to the dramatic situation that Israel is living: It is surrounded by enemies and coming close to ruin. What to do in such a difficult time?

Remember, do not forget. Look at our past, consider what God has done, keep in mind the wonders he accomplished in our favor, always remember his works of salvation: Remember that you were once enslaved in the land of Egypt, from where Yahweh, your God, brought you out with his powerful hand and outstretched arm (Dt 5:15).

This invitation to remember and not to forget is addressed also to us. The forty years spent by the people of Israel in the desert represent our whole life.

A story is told about a boy who refused to go to school. His mother decided to take him there herself. He cried, screamed and protested on the way, and when her mother left, he ran back home. This scene played out over and over again for several days. His parents tried all sorts of arguments but the boy continued to refuse to go to school.

Finally, the parents went to an older and beloved uncle and explained the situation to him. He simply said: Because the boy won’t listen to words, bring him to me. When the boy came to him, the old man did not say anything. He simply picked up the boy, carried him, and held him close to his heart. Then, without saying a word, he put him down. After that, he not only began going to school. He went on to become a great scholar.

What spoken words could not accomplish, a silent embrace did. The Eucharist is God touching us. It is his physical embrace, his kiss, a ritual within which he holds us to his heart.

During our exodus to the heavenly dwelling that lasts forever (2 Cor 5:1), God offers also to us a completely new food, other than those that man has always known and experienced, a food coming from heaven like manna: his Word becomes bread.

The Second Reading refers to a difficult situation of conflicts, different opinions, and lack of unity in the community of Corinth. Saint Paul takes this opportunity to remind the community that it is precisely the broken bread that creates unity. Through the Eucharist, we are not only in union with Jesus but also with the Church, the Body of Christ. This means that we do not journey alone. By being incorporated into the Body of Christ, we give support to and receive it from the Christian community, especially in times of trials and sickness.

The Church teaches us that we should strive to receive the Eucharist daily. But in addition, we cannot forget that Christ’s presence in the Eucharist gives us the opportunity to pray before him in a special way. Our Father Founder, like many saints, has urged us to do so as often as possible. There are many forms of Eucharistic Adoration in common, but in addition, the personal visit to the Blessed Sacrament is something that we should take advantage of since it does not remain unanswered. Christ always welcomes our small act of generosity, offering a few minutes of our time and then responding Himself touching our hearts in an unforeseeable and effective way.

Apart from the wonderful and well-known stories which are called ” Eucharistic miracles”, it is important to recognize that there are many intimate, personal Eucharistic miracles that take place day by day in those who believe in the promise of Christ. Therefore, let this reflection conclude as it began, with a moving example of love for the Eucharist and the effects of that profound acceptance of the Body of Christ.

At the beginning of the XI century, a young Episcopalian woman accompanied her husband, a merchant, to Italy, leaving four of their five children at home with family members. They had sailed for Italy hoping that the change in climate might help her husband, whose failing business had eventually affected his health adversely. Tragically he died in Livorno.

The grieving young woman was warmly received by an Italian family, business acquaintances of her deceased husband. She stayed with them for three months before she could arrange to return to America. She was very impressed by the catholic faith of her host family, especially their devotion to the Holy Eucharist: the reverence with which they received Holy Communion, the awe they showed toward the Blessed Sacrament on feast days when the Eucharist was carried in procession. She found her broken heart healed by a hunger for this mysterious presence of the Lord, and, upon returning home, requested instruction in Catholic Faith.

Soon after being received into the Church, she described her first reception of the Lord in the Eucharist as the happiest moment of her life. It was in St. Peter’s Square on September 14, 1975, Pope Paul VI canonized this woman, Elizabeth Ann Seton (1774 – 1821), founder and apostle of education and hospitality, as the first native-born saint of the United States. The Eucharist for her was a sign and cause of union with God and the Church.