by f. Luis Casasús, General Superior of the Idente missionaries.

New York, February 24, 2019.

Seventh Sunday in Ordinary Time

1st Book of Samuel 26,2.7-9.12-13.22-23; 1 Corinthians 15,45-49; Saint Luke 6,27-38.

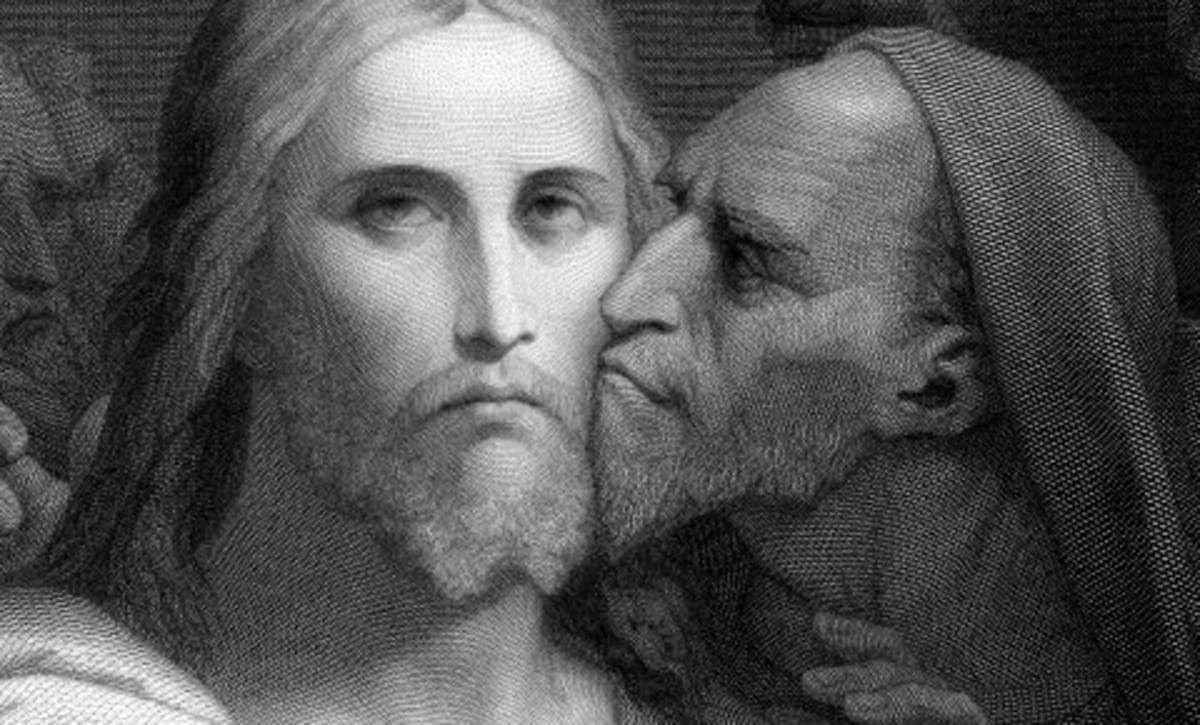

Judas Iscariot always received from Jesus a sign of confidence, a gesture of trust, a confirmation of His mercy. And Christ’s attitude toward this betraying disciple is the most extreme example of evangelical active and wise mercy.

What are the traits of Christian forgiveness? Today the Readings offer many answers. Let us reflect on some of them.

1. Forgiveness is something deep in our true nature. It has been repeated that there are two “natural” ways of dealing with aggression: fight or flight. But we have been created in the image and likeness of a God who is merciful. When we talk about Adam and Eve, we always refer to the original sin, but just as original and fundamental was the forgiveness our first fathers received from God. Adam and Eve were forgiven by God but nevertheless still banished from the Garden of Eden. The Book of Exodus describes God as merciful and gracious, forgiving iniquity and transgression and sins. It also adds yet not without punishing (Ex 34: 7).

Today’s Second Reading says: Just as we have borne the image of the earthly one, we shall also bear the image of the heavenly one. This forgiving nature, received from the beginning, is deeper and more powerful than our instincts. We cannot say that a coconut is hard. This is imprecise and inaccurate. A coconut is very hard on the outside, but the interior is a soft tissue with a clear and delicious fluid.

An elderly religious Hindu man used to meditate every morning under a large tree on the banks of the river. One morning after he had finished his meditation he noticed a large scorpion floating helplessly on the strong current of the river. The scorpion became caught in a tree’s long roots that extended into the river bed. The more it struggled to free itself, the more entangled it became in the twining roots. The man reached out to free the captive creature and, as soon as he touched it, the scorpion lifted its tail and stung him. But the man reached out again to try and free it. A young man was passing by and saw what was happening. He shouted out: Hey old man, what’s wrong with you? You must be mad! Why bother risking your life to save such an ugly useless creature? The elderly man turned to the young onlooker and in his pain asked: Friend, because it is the nature of the scorpion to sting, why should I give up my own nature which is to save?

Sometimes the harm suffered is so horrible, that perhaps we do not want anyone to forgive what has been done. In other cases, we have enemies whom we cannot eject from our lives. One woman struggles with the reality of her mother as her abuser and admits that even thought her mother is dead, she’s haunted. Forgiveness will probably not happen. Another woman has adopted a foster child and realizes that she will have to put up indefinitely with visits from her enemies: the child’s dysfunctional, manipulative, and sometimes cruel family members. It is precisely in these cases where we need to remember that we are not alone in the effort to forgive what seems unforgiveable.

2. Forgiveness is THE way to spiritual freedom and unity. Forgiveness is letting go of the story we made up so we can experience the truth that sets us free. Only then can we be unchained from our past, and freed for a fruitful trip on our spiritual path. Not only that; forgiveness holds us together through good times and bad times, and it allows us to grow in mutual love. The temptation is to cling in anger to our enemies and then define ourselves as being offended and wounded by them. Forgiveness, therefore, liberates not only the other but also ourselves. It is the way to the freedom of the children of God. The gift of forgiveness is creative of community; the community lives from and extends this gift.

A pilgrim was travelling through a land devastated during the war, and cruelly divided by the post-war struggle between rebel forces and loyalists that had only just drawn to a close. Arriving in a village, he was given hospitality by an old man called Leo. The Leo ‘s house had been burnt down, and so he received his guest in the shed that was now his home.

The pilgrim learnt Leo’s story. His two eldest sons had joined the rebel forces. But some villagers betrayed their hiding-place; they were captured and never seen again. About the same time, his wife died from starvation. After the war, Leo was living alone with one of his married daughters and her baby son. She was expecting her second child in a few weeks. One day he returned home to find his house set on fire by loyalists. I was in time to see them drag my daughter out and kill her; they shot all their bullets into her stomach. Then they killed the little boy in front of me.

Those who did these things were not strangers, but they were local people. Leo knew exactly who they were, and he had to meet them daily. I wonder how he has not gone mad, one of the village women remarked to the pilgrim. But Leo did not in fact lose his sanity. On the contrary, he spoke to the villagers about the need for forgiveness. I told them to forgive, and that there exists no other way, he said to the pilgrim. Their response, he added, was to laugh in his face. When, however, the pilgrim talked with Leo’s surviving son, the latter did not laugh at his father, but spoke of him as a free man: He is free because he forgives.

Two phrases stand out in this account:

* There exists no other way. Certain human situations are so complex and intractable that there exists only one way out: to forgive. As Mahatma Gandhi observed, “an eye for an eye” leaves the whole world blind. Solely through forgiveness can we break the chain of mutual reprisal and self-destroying bitterness. Without forgiveness, there can be no hope of a fresh start. Surely his words apply also to many other situations of conflict.

* He is free because he forgives. Yes, where there is forgiveness … there is freedom. If only we can bring ourselves to forgive – if we can at least want to forgive – then we shall find ourselves in an atmosphere of heavenly freedom. This is the lesson of today’s First Reading.

When feel we cannot forgive what has been done to us, we still can use the words of Christ: Father forgive them, they do not know what they are doing. We can ask that God to first do the forgiving … We will find that our anger, our sense of ‘poor me’, will gradually diminish on its own without our having to do much else.

This reminds me of our Founder`s proverb: The men’s forgiveness is not so successful as God’s (Transfigurations). Jesus forgave the adulterous woman and the penitent thief. Neither do I condemn you is the passive side of our Lord’s attitude to contrition. Today you will be with me in Paradise is its active side.

Forgiveness precedes conversion. God does not forgive us because we repent; rather we repent because God forgives us. The Prodigal Son was able to repent because he remembered his father who was loving even to his hired workers: Coming to his senses he thought: How many of my father’s hired workers have more than enough food to eat. It is the father’s love that moved him to “go back home,” to repent.

That is also what happens, sooner or later, when we forgive:

Decades ago, in a small town, a Christian couple lost their only son because of a young drunk driver. Though they were sorrow stricken, they knew their son was with God for he had known Him. With sorrow they went to the jail to visit the young man who had killed their son. They found out he was from a broken family and had never received true love. They decided to visit him daily and share the Gospel with him. Eventually they adopted him as their son. The young man was greatly touched. Not only did he become a Christian, but later dedicated himself to full time apostolate. This young man did not receive love from his own family, but received perfect love from the family who because of him lost their beloved son.

3. Forgiveness is creative and a fruit of our victory over fear.

Mother Teresa, the saint of the Calcutta slums, went with a small child to a local baker and begged some bread for the hungry lad. The baker spat full in Mother Teresa’s face. Undaunted, she calmly replied: Thank you for that gift to me. Do you have anything for the child?

She responded, neither with counter-violence nor with flight, but rather with a provocative gesture meant to draw the aggressor into a new spiritual consciousness.

Forgiveness is not just about saying don’t worry about it, nothing happens, or not holding a grudge.

Forgiveness creates a new way to be together. It is not centered in myself, but in the mission which I have to discover in the daily jungle of misunderstandings and opposition and resistances. Our lives will be richer once we realize that life –especially spiritual life- is not all about me.

Especially, God’s forgiveness is creative: it makes him who has become guilty free of all guilt. God gathers the guilty man into His holiness, makes him partake of it, and gives him a new beginning. It is to this mystery that man appeals when he acknowledges his sins, repents of them, and seeks forgiveness.

Why do we not embrace the risk of forgiving? Precisely because we are afraid of new things, of a new life that forgiveness demands of us. Faith is the opposite of fear. Perfect love casts out fear, and faith connects us to that perfect love. When Jesus calmed the storm, he questioned his disciples: Why are you so fearful? How is it that you have no faith? (Mk 4:40) Yes, the opposite of fear is not courage but faith. Fear in many guises is one of the major barriers to love. Jalal Uddin Rumi, the 13th century Sufi mystic said: Your task is not to seek for love, but merely to seek and find all the barriers within yourself that you have built against it.

Strictly speaking, it is paradoxically the healthy fear or reverential fear of God which overcomes other fears and is intimately connected with faith. It is a kind of healthful fear that makes one’s faith in God bold. For Christians, it is faith that leads beyond ordinary fear, death and intimidation. It is a faith that turns impossible circumstances into hope. And it is faith that makes believers strong in the face of attacks and humiliation. This is the experience of the saints:

St. John Climacus (579-649) wrote: Whoever has become a servant of the Lord fears only his Master. But whoever is without the fear of God is often afraid of his own shadow. Fearfulness is the daughter of unbelief.

St. Ephraim the Syrian (306-373), a true teacher of repentance, says: Whoever fears God stands above all manner of fear. He has become a stranger to all the fear of this world and placed it far from himself, and no manner of trembling comes near him.