Gospel according to Saint Matthew 4:1-11

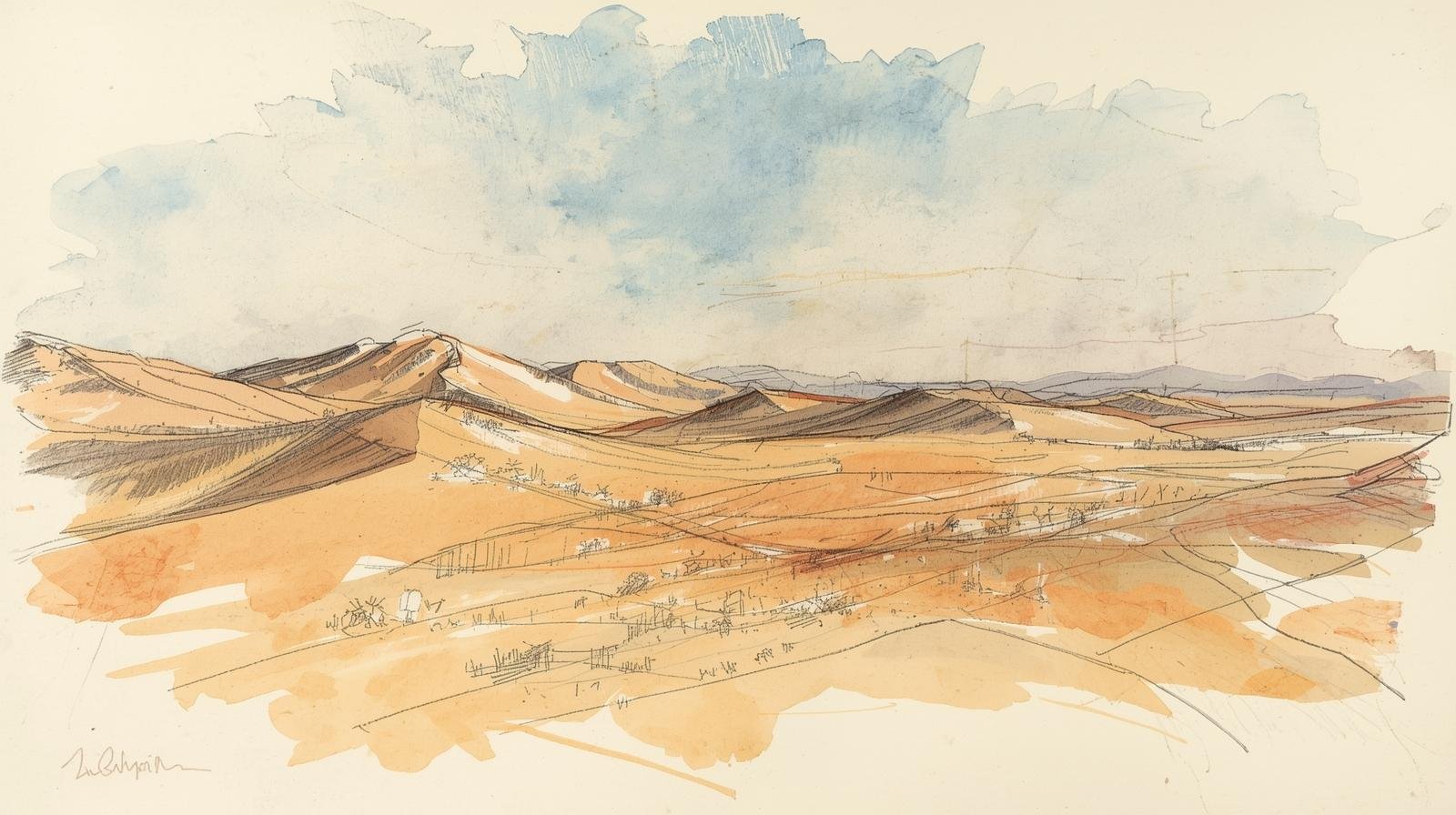

At that time Jesus was led by the Spirit into the desert to be tempted by the devil. He fasted for forty days and forty nights, and afterwards he was hungry. The tempter approached and said to him, “If you are the Son of God, command that these stones become loaves of bread.” He said in reply, “It is written: ‘One does not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes forth from the mouth of God.’”

Then the devil took him to the holy city, and made him stand on the parapet of the temple, and said to him, “If you are the Son of God, throw yourself down. For it is written: ‘He will command his angels concerning you’ and ‘with their hands they will support you, lest you dash your foot against a stone.’” Jesus answered him, “Again it is written, ‘You shall not put the Lord, your God, to the test.’”

Then the devil took him up to a very high mountain, and showed him all the kingdoms of the world in their magnificence, and he said to him, “All these I shall give to you, if you will prostrate yourself and worship me.” At this, Jesus said to him, “Get away, Satan! It is written: ‘The Lord, your God, shall you worship and him alone shall you serve.’” Then the devil left him and, behold, angels came and ministered to him.

The devil: just a metaphor?

Luis CASASUS President of the Idente Missionaries

Rome, February 22 2026 | First Sunday of Lent

Gen 2: 7-9; 3,1-7; Rom 5: 12-19; Mt 4: 1-11

On this first Sunday of Lent, we are invited to prepare ourselves for the celebration of the Paschal Mystery, the passion, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. Easter is a celebration of life. But, as St. Paul says: Sin entered the world through one man, and through sin came death (Rom 5:12).

Therefore, Lent is a time when we seek to fight against the devil, temptation, and sin, which bring spiritual death to the world. But surely, we have a very poor idea of what this struggle with the devil is, because we do not pay close attention to Christ’s attitude in the temptations recounted in today’s Gospel.

Perhaps we will understand it better by starting with two examples that have NOTHING to do with the devil.

֍ Imagine that someone, in an argument, says to you in an ironic tone: Sure, you always have to be the smartest one.

If you don’t give it much importance and it doesn’t hurt too much, it’s probably NOT a weak point.

But if it burns inside you, if you feel the urge to justify yourself, explain yourself, defend your image… there’s a clue there. The other person, your “adversary,” has not created the wound; rather, they’ve touched it. What the attack reveals is not so much their malice as your attachment: in this case, the need to be recognized as righteous, cultured, or morally superior.

֍ Another different example. Someone deliberately excludes or ignores you, and you believe you have something to contribute. No one insults or attacks you directly, but that hurts more than direct criticism. This shows that one of your weaknesses is the fear of not being seen, of not mattering, of not being considered.

In both cases, your adversary acts as an uncomfortable mirror: they reveal how distressing it is to believe that there is something you want to protect, they point out what you have not yet integrated, they make you see how you depend on something external to sustain you.

The conclusion is that whoever is considered an adversary, even if they may be an enemy, is always also a revealer, a kind of indicator. Not because they are morally right, but because they know—sometimes intuitively—where there is a weak spot in you, so they can attack.

From a theological and anthropological perspective, Christ’s temptations not only speak of Him, but also serve as a mirror for human beings. They are presented as evidence of where our deepest weaknesses tend to lie.

If we look closely, each temptation points to a very specific human limitation:

֍ Need and fear of deprivation. “Turn these stones into bread” touches on hunger, survival, anxiety about material things, and the activities in which we feel comfortable. It is the temptation to reduce life to the immediate: if I have this, I am fine. To paraphrase Nietzsche ironically, we could say: It is something very human, all too human.

֍ The desire for power and control. “I will give you all the kingdoms of the world” reveals the fascination with domination, with ensuring success without going down the difficult path. It is the temptation to instrumentalize even what is good and positive… even the neighbor I say I love.

֍ The search for absolute security and recognition. “Throw yourself down and let the angels catch you” speaks of wanting proof, clear fruits of my efforts, guarantees, divine or human applause. It is the temptation to force God (or life) to prove that I am protected.

In this sense, temptations describe human beings in extreme situations: hunger, loneliness, uncertainty, vulnerability… Christ does not appear alien to all this, but rather as someone who fully embraces the human condition and experiences it without denying it.

So, rather than a moralizing scene, the story of Jesus’ temptations is an existential portrait. They speak to us of the strength of our attachments, especially to the world and to the ego. Temptations do not diminish Christ, or you, or me; on the contrary, they dignify us, and if we know how to use them, they become an element of our mystical life, something that transforms us. Our Founder, Fernando Rielo, encourages us to look at the Diabolical Signs, which do not have to be spectacular, but reveal the sufferings of our soul that we must take advantage of in an appropriate way, especially apathy, aridity, and vacillation.

The Holy Spirit gives us the light so that a situation in our soul that could lead to an attraction to evil becomes an impulse that brings us closer to the Divine Persons.

* An example of how a saint made positive use of aridity is Teresa of Calcutta.

For decades she experienced profound spiritual aridity: an almost total absence of inner consolation, a sense of God’s silence, even the impression of being “rejected.” And yet, outwardly, she persevered with impressive fidelity in her mission among the poorest of the poor.

What is interesting is how she took advantage of that aridity, which she did not interpret as failure or punishment, nor did she use it as an excuse to withdraw into herself.

She herself wrote that her inner darkness allowed her to better understand the loneliness of the poor, the sick, and the dying. In other words, aridity ceased to be an obstacle and became a true bridge: If I feel abandoned, I can be closer to the abandoned.

Another example is St. John of the Cross. In the Toledo prison, he experienced an extreme spiritual night: isolation, humiliation, absolute dryness. Instead of fleeing from that experience, he contemplated it and turned it into a valuable spiritual tool. From this arose the idea of the “dark night,” which is not a sterile void, but rather a painful grace that purifies desire and frees it from false supports.

In both cases, there is something in common: aridity is not “resolved,” it is traversed. And in doing so, the aspiring saint discovers that the most mature faith is not based on what one feels, but on what one chooses.

* A model of how to embrace apathy profitably is Saint Thérèse of the Child Jesus. In the last years of her life, she describes states that today we would clearly call apathy: a lack of taste for prayer, inner fatigue, a lack of enthusiasm even for things that used to inspire her. It was not rebellion or intense sadness; it was rather a flat dryness, a “I feel nothing.” But she did not wait to “feel” in order to love and decided to transform apathy into a field of exercise for her intentions, carrying out the smallest acts without emotional support.

She smiles sincerely when the person in front of her does not please her, she prays calmly when she feels nothing special.

Teresita knew that this pleased God, because she was no longer sustained by pleasure, but by naked choice. She said that these “tasteless” acts were purer gifts, because they were not given for comfort, but for love.

We could also mention St. Francis de Sales, who speaks of dry devotion and affective indifference. He himself confesses to periods when he felt no impulse toward God, but he insists on something very concrete: quiet fidelity in the ordinary is worth more than passing outbursts.

In both cases, apathy is not combated by forcing oneself to feel, but by redefining what it means to love. Not as an emotion, but as a free and persevering act.

* A prototype of how to make positive use of vacillation is Saint Peter. He is, par excellence, the saint of vacillation. He does not doubt his reason, but when the pressure becomes overwhelming. First, he promises total fidelity, and hours later, he denies the Master; not out of malice, but out of fear, confusion, and a lack of inner strength.

What is interesting is what he does with that vacillation. After his denial, Peter does not harden his heart or justify himself. He weeps bitterly, that is, he allows his vacillation to break him down. There he learns something decisive about himself, that his love was sincere, but his strength was not as great as he thought.

And Jesus takes advantage of exactly that weakness; when he rehabilitates him, he does not ask him for heroics or future assurances. He asks him a humble and repeated question: Do you love me?

The devil was more successful with Judas Iscariot: he removed from his soul the remorse for the petty thefts he was committing (Jn 12:4-6), thus erasing his desire for conversion and separating him from the group of disciples and from Christ himself, ruining a vocation that would have been as vibrant as that of his companions.

—ooOoo—

But does the devil exist?

It is not a question of giving an answer about his possible nature, which has been discussed at length in theology. What matters to each of us is to be aware that our constant inclination to take the place of God, to be independent of Him, almost always without the impression of acting with bad intentions, has all the characteristics of a seductive person, with the apparent purpose of doing us good.

Let us remember, in fact, that in the Gospel, there is an occasion when Christ calls Peter “devil” (Mt 16:23), because at that moment he acts as an obstacle to Jesus walking the path that will lead him to the gift of his life.

Peter presents himself as Jesus’ friend; he expresses his good intentions, so that Jesus will not go to Jerusalem and save his life, thus pushing him to separate himself from the will of the Father.

The word “devil” comes from the Greek διάβολος (diábolos), interpreted as someone who ‘casts’ lies or discord, or “the one who separates” and prevents the relationship of love between God and people.

We should recognize that there is a true “personality,” a distinctive behavior in the set of all the movements of our soul that originate in passions and instincts.

Let us therefore have a truly scientific attitude: let us look for regularities and patterns in our tendency to occupy God’s throne, either because we are wicked or because our supposed virtues make us believe we are self-sufficient. Surely, the most coherent conclusion is that behind all this there is a personality that resembles the one presented today in the Gospel at the end of Jesus’ 40 days in the desert, where he was—let us not forget—sent by the Holy Spirit to be tempted by the devil.

_______________________________

In the Sacred Hearts of Jesus, Mary and Joseph,

Luis CASASUS

President